For decades Central Asia was ignored by both the Soviet Union and the emerging new world order afterwards as key to an economic link between China and Eurasia. It was Beijing that first saw an opportunity to bring those countries together under a new coalition. Thus in 1996 with five members, the Shanghai Five was born as a modest attempt by China to build an emerging political and economic coalition … writes Osama Al Sharif

Central Asia promises to be the next big thing in global geopolitical evolution. It could be the hub of the world’s major economic Promised Land or it could easily turn into ground zero for the next apocalyptic world showdown. It all depends on the outcome of Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Central Asia today is defined by five former Soviet republics; Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Each has its own troubled ties with the Russian Federation. Break up from the rump Soviet Union was relatively easy, but historical skeletons in the cupboard threaten to conjure up old rivalries. In so many the buried corpses of Joseph Stalin, who forged the current borders by force and at a huge humanitarian cost, may soon rise like zombies to haunt the current leaders.

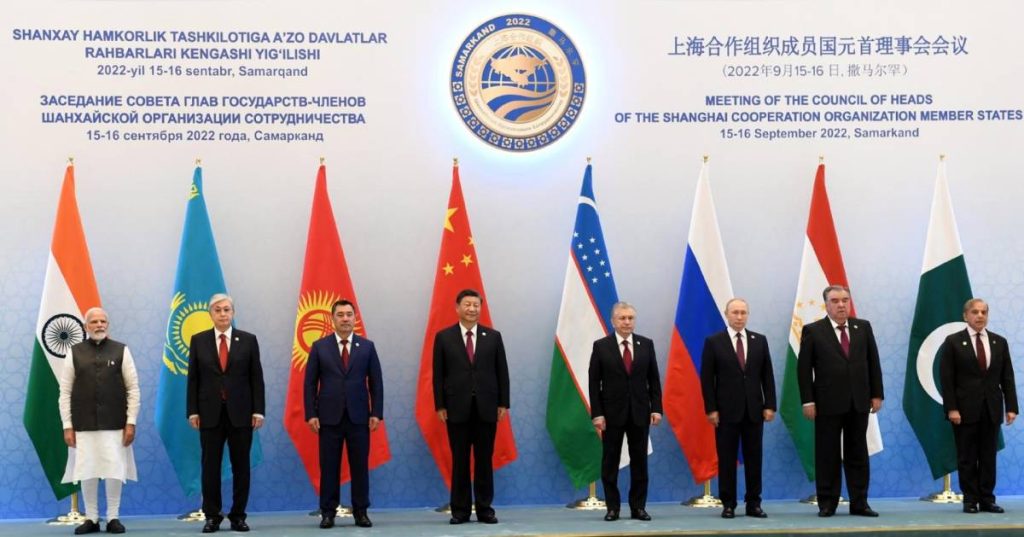

For decades Central Asia was ignored by both the Soviet Union and the emerging new world order afterwards as key to an economic link between China and Eurasia. It was Beijing that first saw an opportunity to bring those countries together under a new coalition. Thus in 1996 with five members, the Shanghai Five was born as a modest attempt by China to build an emerging political and economic coalition. The Shanghai Five consisted of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan. Over the years, and with China as a founding member and major economic power, the SCO has expanded slowly but surely since 2001, boasting nine member states, with Pakistan and India joining in 2017 in addition to Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Today this economic coalition is the world’s largest organization with more than 30 percent of the globe’s GDP. But still few people have heard of it. The SCO has expanded slowly but surely since 2001, boasting nine member states, with Pakistan and India joining in 2017 in addition to Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

At least five other nations, including the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt have been invited as dialogue partners. Iran signed its membership forms this month and will officially join by 2023.

As much as this new coalition presents serious challenges to beleaguered European Union (EU) and other regional groupings like ASEAN, the challenge is that it could easily be penetrated.

Even though the group now covers 60 percent of the area of Eurasia and 40 percent of the world population with Central Asia featuring as its most promising growth region; a strategic part of Beijing’s Belt and Road global initiative, the problem is that with the Russian war in Ukraine it is still vulnerable.

In the recently held summit in the Uzbek capital Samarkand, it was clear that many members were hesitant to side with Moscow in its war in Ukraine. That was clear in the position of China’s President Xi Jinping and India’s Prime Minister and India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Both did not offer support to Vladimir Putin’s war and opted for a diplomatic solution to the conflict.

While India and China prefer to focus on international trade and regional cooperation instead of a showdown with the West, Putin seems to be held hostage by ideological schisms that are a relic of the Cold War.

This is where Central Asia becomes a key factor in the current geopolitical confrontation. For starters some countries in the region have more business ties to Europe than to Russia. Attempts to present the coalition as anti-western were derailed by the host country, Uzbekistan, whose leader was clear in stating that the SCO is not an anti-western alliance, although the leading members, Russia and China, have major issues with the United States and Europe.

The reality is that a number of Central Asian members have important trade ties with the west. For China, these states present themselves as a bridge between East Asia and the EU.

The Central Asian republics represent a soft underbelly for Russia which seeks to buffer its Eurasian frontiers. The recent border skirmishes between Azerbaijan and Armenia are a test to the Kremlin’s ability to keep the peace among former republics. Same thing with the flare up between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan over border disputes. These old disputes could present a major challenge to the Kremlin as it seeks to win a war in Ukraine.

The reality is that Central Asian republics, with huge natural sources, could be the bridge that China seeks to build between the East and Europe as part of its ambitious Belt and Road initiative. But the Russian war in Ukraine could derail such plans. Russia may have to deal with eruptions along its southern borders that could trigger border wars in the old Central Asian republics. That is not what China wants now. The fact is that Putin may find his foray into Ukraine costing him much more than he is willing to pay.

(Osama Al Sharif is a journalist and a political commentator based in Amman)