The true turning point came when major Indian companies stepped in with better preservation and packaging technologies. ITC led the way with its ‘Kitchens of India’ line, offering restaurant-style dishes from icons like Bukhara and Dum Pukht

The microwave oven ushered in the first wave of convenient ‘heat and eat’ meals in India. Though it wasn’t ideal for the multi-step cooking typical of Indian recipes, it found a place in homes as a reheating tool for leftovers or takeaways. Some used it for boiling potatoes or warming beverages, but overall, the microwave never became central to Indian kitchens. Still, it planted the idea of convenient meals in the Indian mind.

Meanwhile, in the West, TV dinners became the norm, thanks to canned food innovations post-WWII. Though these meals were often bland and nutritionally lacking, they freed millions from daily cooking. In India, nostalgia-driven NRIs initially relied on tinned foods like ‘sarson da saag,’ though these offerings lacked the richness of home-cooked fare.

The true turning point came when major Indian companies stepped in with better preservation and packaging technologies. ITC led the way with its ‘Kitchens of India’ line, offering restaurant-style dishes from icons like Bukhara and Dum Pukht. These products, free of artificial additives, needed just a quick heat-up to serve. Dining on Dal Bukhara or Chicken Chettinad at home suddenly became affordable and accessible.

Others followed quickly. Neighborhood butchers began offering pre-marinated meats, while companies like The Taste Company brought out meal kits like sambar rice and prawn rice, perfect for solo eaters tired of bland tiffin services. MTR and Haldiram revolutionized the space further, offering everything from quick breakfast options to regional favourites like Rajma, Kolhapuri Mutton, and Poha.

Even in-flight dining was transformed, with self-cooking meals that needed only hot water and a few minutes to prepare—ideal for travel. Inspired by Japanese innovations, self-heating packaging briefly appeared in India but struggled to suit local cuisine or pricing models.

Despite these conveniences, most Indians still prefer freshly made home food. While ‘heat and eat’ products are handy, they often lack the depth and satisfaction of a home-cooked meal. Even classics like Poha or Upma are quick and easy to prepare from scratch, reducing the appeal of ready-made versions.

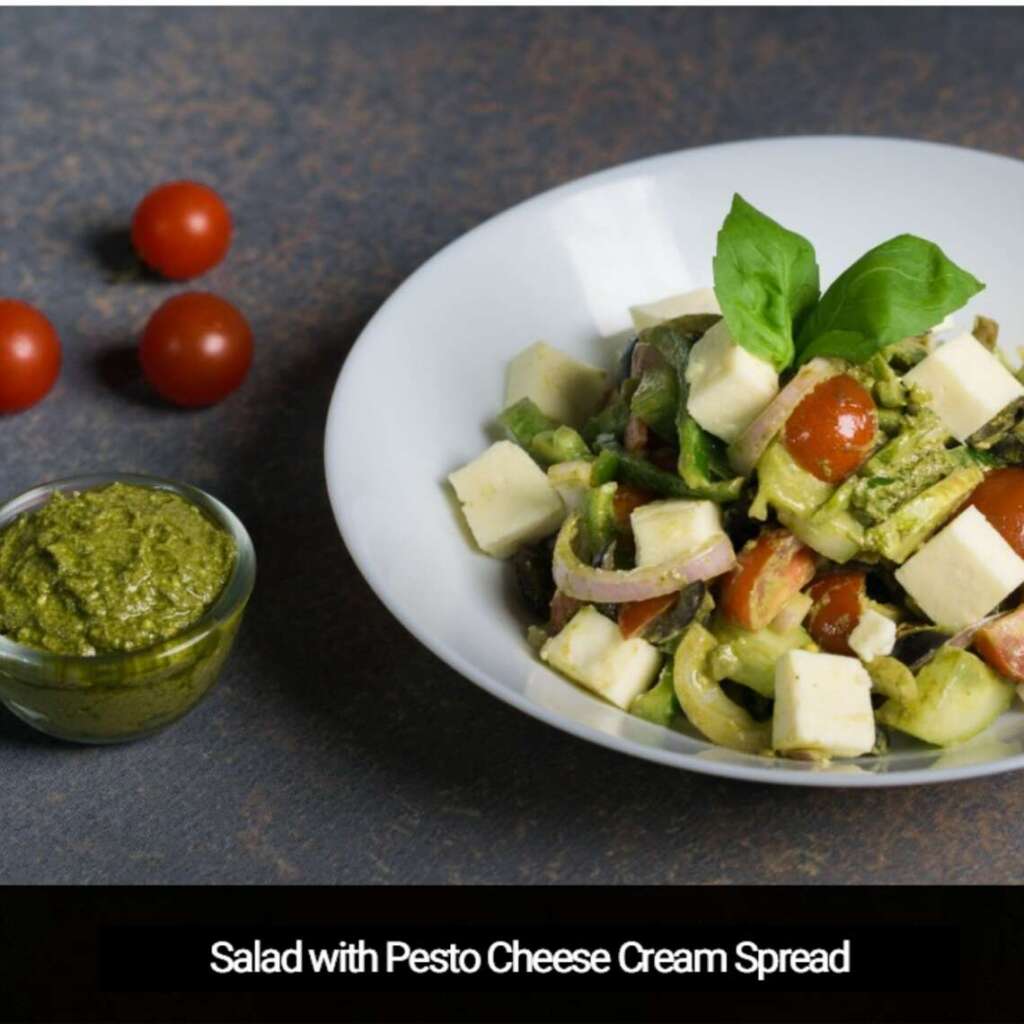

This has led to the rise of the “Ready to Cook” concept—a balance between convenience and taste. Companies like Quickish, based in Hyderabad, are redefining this segment. Their offerings span from Indian favorites like Dal Makhni and Chicken Malai Tikka to global dishes like Korean Grilled Chicken, Moroccan Fish, and Pesto Cottage Cheese Steaks. Prices range from ₹375 to ₹575, and portions are generous, typically serving two.

These meals come expertly marinated and use high-quality ingredients without artificial preservatives. Though their shelf life is shorter (3–4 days refrigerated), the flavor and freshness make up for it. They also save time by eliminating prep work, while delivering restaurant-quality food at home. With rising demand for convenience without compromising on quality, “Ready to Cook” seems poised to lead the next culinary revolution in India. If packaging technologies improve shelf life without affecting taste, this trend could very well dominate the modern Indian kitchen.