The two non-Arab regional powers have sought to unite their voices in support of the Palestinians, but their visions differ significantly. Turkey supports the creation of a Palestinian state based on the 1967 borders, while Iran refuses to recognise Israel and proposes a joint state for Muslims, Jews and Christians, writes Mohammed Anas

Last week’s Organisation of Islamic Cooperation/Arab League failed to find a consensus among member states to adopt a unified stance on the Israel-Gaza conflict. It however signalled that the competition and cooperation ties between Turkey and Iran – two most vocal and active countries of the region – will find common ground to deepen ties and counter Israel.

One common ground that both Ankara and Tehran have found is that they have refused to label Hamas a terrorist organisation. Both in fact have been supporting and will likely spruce up the organisation in whichever way it will exist in future.

Turkey calls Hamas a “mujahideen liberation group” and Iran sees it a “resistance force which is out to liberate Al Quds (Jerusalem) from the Zionist control”.

Both Turkey and Iran seek strong steps from the Muslim world against Israel and the United States as the daily reports of killing of Palestinians are trickling in and the anger of common Muslims is mounting day by day.

The two non-Arab regional powers have sought to unite their voices in support of the Palestinians, but their visions differ significantly. Turkey supports the creation of a Palestinian state based on the 1967 borders, while Iran refuses to recognise Israel and proposes a joint state for Muslims, Jews and Christians.

Interestingly, while Iran has no diplomatic relations with either Israel or US and faces harshest sanctions levied by the US and its Western allies, Turkey continues to maintain ties with both. Turkey even hosts a key US military base and has robust trade ties with Israel. The gas-oil pipeline originating from Azerbaijan to Israel routes through Turkey.

Will partnership with Tehran turn the tables for Ankara?

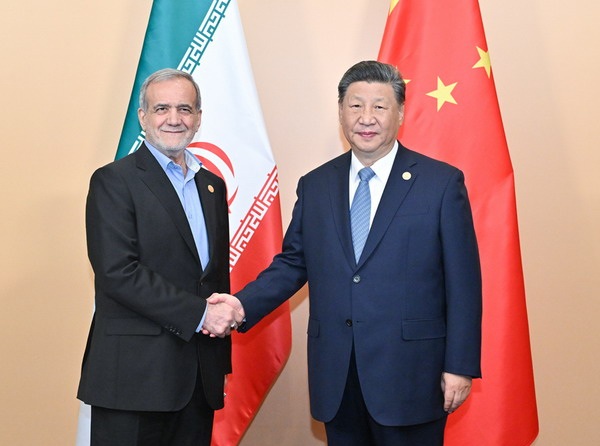

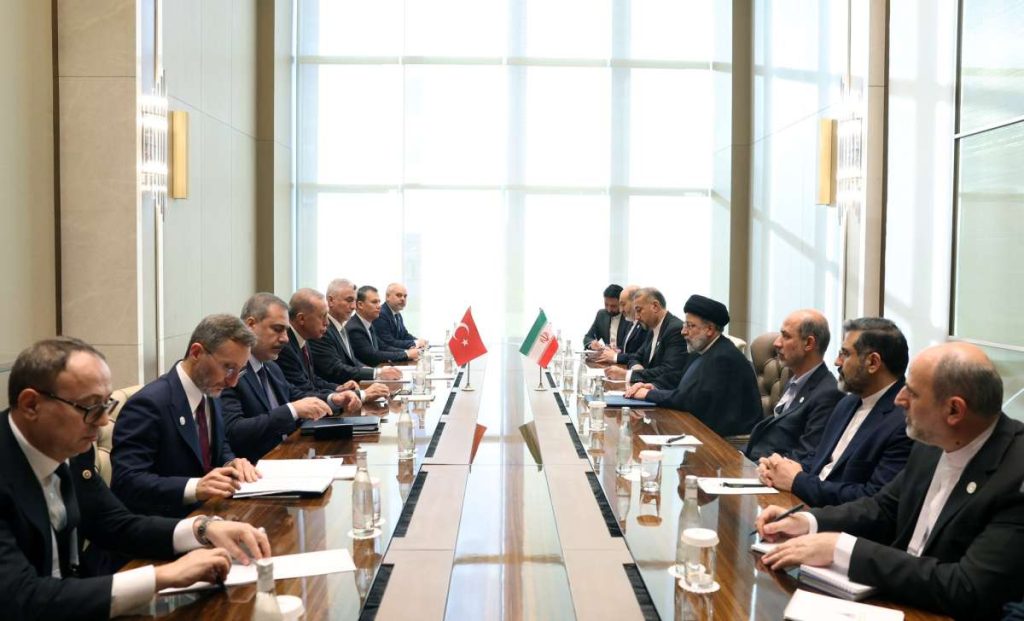

The Saturday’s huddle Riyadh didn’t only see President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi exchanging customary pleasantries, officials from both the countries assembled to purportedly discuss future course of action.

It was announced later that Raisi will visit Turkey by the end of November. It will be on the heels of Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian’s visit to Ankara earlier this month.

Abdollahian said in Ankara that the two sides had agreed to boost border security, establish new border crossings and set up free trade zones as well as convene the bilateral High-Level Cooperation Council.

The talks during Raisi’s visit, according to Turkish and Iranian media, will have a wide-ranging agenda, including Syria and the Caucasus, transboundary waters and fighting terrorism.

Iranian media is also citing Turkey’s stance to claim that Iran is not alone in its Palestinian policy.

Some observers of the West Asian geo-political equation however are not ready to read too much into the possibility of a Turkey-Iran diplomatic or strategic duet.

“Turkey and Iran have been in a complex competition and cooperation vortex of regional conflicts, be it in Iraq, Syria or Azerbaijan. It is true that the ongoing Israeli assault on Gaza and deaths of innocents have forced both these countries to look beyond personal interests and unite for a joint cause of Palestinians that is the most pressing issue in the region right now. Plus, both these non-Arab countries are also opposed to the US-led regional order. However, a long-term sustainable cooperation between the two doesn’t seem plausible given sharp faultlines that exist in Syria and Iraq,” said Pervez Bilgrami, a West Asia expert, while talking to India Narrative.

Professor Manjari Singh of Amity University, Noida, feels that both Iran and Turkey have sought “interventionist” approach to prevent Israeli blitzkrieg in Gaza and even arming the Palestinian fighter groups may be an option for them, and also that it may not stop there and escalate further.

“There’s already a nexus in place between Iran and Turkey and that the response of many Arab countries, especially the Gulf States, towards Israel seem too mild to them, the two countries along with like-minded countries like Algeria may plunge into the ongoing war in a more intense way. There is a likelihood that their ‘interventionist’ approach may not necessarily stop at merely arming the Palestinians but they may step into direct confrontation with the Jewish state, as the war extends to its next stage,” she told India Narrative.

Mikati’s Peace Plan

Hatching away from the glare of media limelight, Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati has prepared a peace plan to put an end to the Israel-Hamas conflict in Gaza. His peace initiative is the result of hurried tours to Western capitals and visiting heads of states in the Middle East.

In an interview with the Economist, he outlined his scheme.

First, he suggests a five-day humanitarian pause to fighting and in the meantime Hamas would free some of the hostages, civilians and foreigners as priority. At the same time, Israel would keep ceasing fire so that humanitarian aid could be moved to all parts of Gaza. Hamas would also concurrently stop firing rockets. If this first experiment works, Mikati suggests that the second stage would be to make it permanent. Later, Mikati hopes, Israel and Hamas could opt for further prisoners-for-hostages swap with the help of intermediaries.

Western and regional leaders would then begin work on the third stage: an international peace conference for a two-state settlement for Israel and Palestine. “We will consider the right of Israel and the right of the Palestinians,” Mikati told the Economist, adding, “It’s time to make peace possible in the whole region.”

Mikati hopes that once such a peace plan would take off and find permanent regional backers, armed groups like Hamas and Hezbollah can be asked to shun arms and join the mainstream of regional politics and development.

If it can get off the ground, Mikati’s proposal would channel the worst violence Israelis and Palestinians have seen in decades into the most serious peace effort since the collapse of the Oslo Accords.

Flight and Descent of Peace Formula

The Mikati plan’s success hinges on Western support, which remains uncertain. While some nations advocate for a humanitarian ceasefire, key players like the US, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and Italy, emphasise temporary “humanitarian pauses,” upholding Israel’s right to self-defense. This stance could undermine the potential backing for Mikati’s proposal.

Foreign Policy magazine acknowledges the plan’s imperfections, particularly its vague stance on the future of Hamas and its combatants during the ceasefire. Yet, it emphasises the need for global middle powers to assist in refining and supporting Lebanon’s peace proposal.

“It is a plan that is as ambitious as it is unlikely to succeed. But as Israel’s brutal incursion into the Gaza Strip continues, with indications that it could last indefinitely, Mikati’s plan may be the best one we have, and its odds of success are directly correlated with who chooses to join the effort. And it’s certainly better than the modest, fragmented, and incoherent positions of Western leaders to date,” said Justin Ling, a Toronto-based journalist who specialises in West Asia affairs.

In his last leg of tours in the region, Mikati met with the Iranian ambassador in Beirut, highlighting his ability to serve as an interlocutor with Tehran. On Saturday, he met with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who has become the guarantor for aid deliveries to the Gaza Strip. Days earlier, Mikati met with the emir of Qatar, whose country has hosted Hamas’s senior political leadership for the past decade.

Observers say that apart from convincing Western powers, getting Arab leaders on the table with a direct endorsement of the Israeli state would be difficult, yet, they say, it is achievable. Even Iranians could come on board.

“Lebanon is particularly anxious about avoiding broader regional conflict, particularly as it would likely involve Hezbollah, an armed group with 100,000 fighters that operates independent of Mikati’s government. But they’re not the only ones. Destabilisation in the region could be ruinous for Iran’s regime, already facing pressure from years of domestic unrest. Qatar, meanwhile, is keen to flex its regional leadership.

Speaking to the Economist, Mikati was bullish on the idea that he could untangle the complex Arab politics, at least. “If we have (an agreement on) international and comprehensive peace, I am sure (Hezbollah) and Hamas will lay down their weapons,” he said. He further predicted that “the Iranians will be part of a comprehensive peace.”

There is one hurdle in the success of Mikati’s plans: Mikati may have connections, but he lacks clout. And his plan, thus far, has floundered. Mikati has found no converts in the West, at least so far (his plan was unveiled in the beginning of November) Given that Lebanon has no formal diplomatic relations with Israel — a reality that is unlikely to change, given that Beirut is pursuing war crimes charges for the deaths of civilians in Gaza — it will need to win over Israel’s friends.

A confidant of Mikati however has told Lebanese media that his connections in the West, the Gulf and Iran make Mikati uniquely placed to sell an inclusive plan to end “forever war of the Middle East.”