Amnesty exposes global tech firms fuelling Pakistan’s vast surveillance network, where foreign-supplied tools enable censorship, spying, and repression, leaving citizens trapped in a digital panopticon with no escape….reports Asian Lite News

Pakistan’s already fragile democratic space is under severe threat from a growing mass surveillance and censorship infrastructure, enabled not only by state agencies but also by foreign technology companies across China, Europe, North America, and the Gulf.

A damning new report by Amnesty International, titled “Shadows of Control”, reveals how sophisticated surveillance tools supplied by international firms have been embedded into Pakistan’s digital and telecom systems, allowing authorities to monitor, censor, and repress at an unprecedented scale.

The investigation, carried out over a year in collaboration with international human rights groups and media outlets, highlights the extent to which foreign companies are enabling a surveillance regime that Amnesty describes as “dystopian” and “morally indefensible.”

Pakistan’s digital watchtowers

At the heart of the surveillance architecture are two systems: the Web Monitoring System (WMS 2.0) and the Lawful Intercept Management System (LIMS).

The report notes that WMS 2.0 functions as a nationwide firewall, blocking entire websites or throttling internet access whenever the state deems content “unlawful.” Originally installed in 2018 using technology from Canadian firm Sandvine (now AppLogic Networks), the system was later upgraded after Sandvine’s exit from the Pakistani market.

Today, it is powered by technology from Chinese firm Geedge Networks, with additional hardware and software supplied by US-based Niagara Networks and French defence electronics giant Thales. This global patchwork, Amnesty says, has given Pakistan one of the most sophisticated censorship systems outside of China’s own Great Firewall.

Meanwhile, the Lawful Intercept Management System is embedded directly across telecom providers at the insistence of the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority. Developed with core components from German company Utimaco and Emirati firm Datafusion, it allows real-time interception of calls, texts, emails, and browsing histories. Amnesty estimates the system could track as many as four million individuals simultaneously.

Both tools, Amnesty warns, operate with almost no transparency or judicial oversight, placing nearly every internet and mobile user in Pakistan under potential state scrutiny.

A tool for repression

The Amnesty report documents how this technology is being weaponised to stifle dissent. Journalists, activists, and opposition figures are routinely subjected to targeted surveillance.

One investigative journalist recounted how, after publishing a corruption exposé, he found not only himself but also his contacts under constant watch. “Anyone I would speak to, even on WhatsApp, would come under scrutiny,” he said. “Authorities would interrogate them about why I called. Now I go months without speaking to my family, for fear they will be targeted.”

Amnesty’s Secretary General, Agnès Callamard, described the findings as alarming:

“Pakistan’s Web Monitoring System and Lawful Intercept Management System operate like watchtowers, constantly snooping on the lives of ordinary citizens. In Pakistan, your texts, emails, calls and internet access are all under scrutiny. But people have no idea of this constant surveillance and its incredible reach.”

She added that the situation “severely restricts freedom of expression and access to information,” turning legitimate law enforcement tools into mechanisms of mass control.

The foreign connection

While Amnesty condemned Pakistan’s government for its sweeping abuse of digital rights, it also directly criticised the companies supplying the infrastructure. Of the 20 firms identified, only Niagara Networks and AppLogic Networks fully responded to Amnesty’s inquiries, while Utimaco and Datafusion provided partial replies.

Others, including Geedge Networks and Thales, either ignored or refused to engage with the organisation’s findings. Pakistan’s government, meanwhile, did not reply to any correspondence.

Export control authorities in Germany and Canada acknowledged receipt of Amnesty’s queries but did not provide substantive answers. The lack of accountability, Amnesty argued, has allowed global companies to profit from surveillance contracts while turning a blind eye to their misuse.

The report situates Pakistan’s digital clampdown within a broader global trend: the export of surveillance technologies originally designed for counter-terrorism or law enforcement into authoritarian or unstable environments.

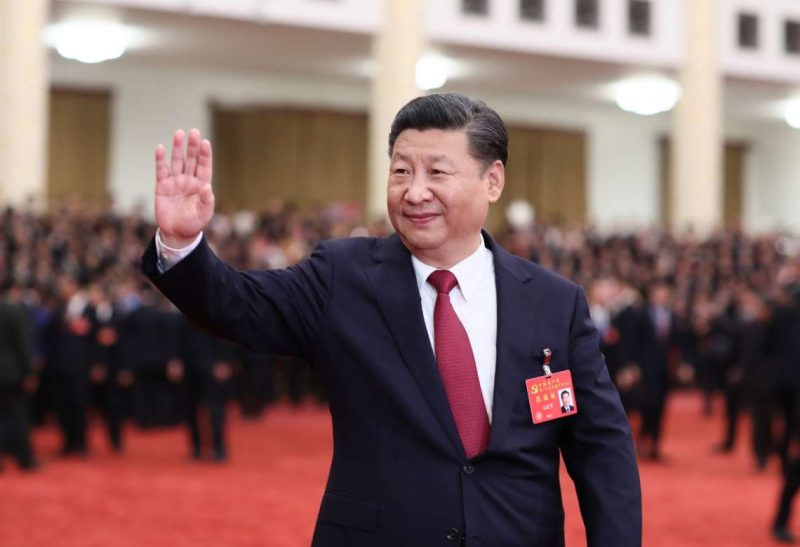

China’s “Great Firewall” has become a commercial blueprint, with Geedge Networks reportedly exporting adapted systems to countries like Pakistan. Amnesty notes that by embedding such systems in telecom infrastructure, states gain permanent, near-total control of digital space.

In Pakistan’s case, this has led to an erosion of democratic freedoms. Social media platforms are frequently restricted; activists find their accounts suspended or throttled; online news portals face abrupt takedowns. The chilling effect is profound, with citizens censoring themselves out of fear of reprisal.

Amnesty’s call to action

Amnesty International concluded its report with urgent recommendations. It called for: stricter global regulations on the export of surveillance technology; greater accountability for companies profiting from authoritarian contracts; stronger human rights safeguards within Pakistan, including judicial oversight and transparency.

“Surveillance technology sold under the banner of security is being turned into an instrument of repression,” Callamard said. “This is not only illegal under international law but morally indefensible.”

For Pakistan’s civil society, already under pressure from political turmoil and economic instability, the report underscores the scale of the challenge. While governments and corporations point fingers at each other, ordinary citizens remain trapped in the shadows of an all-seeing state.