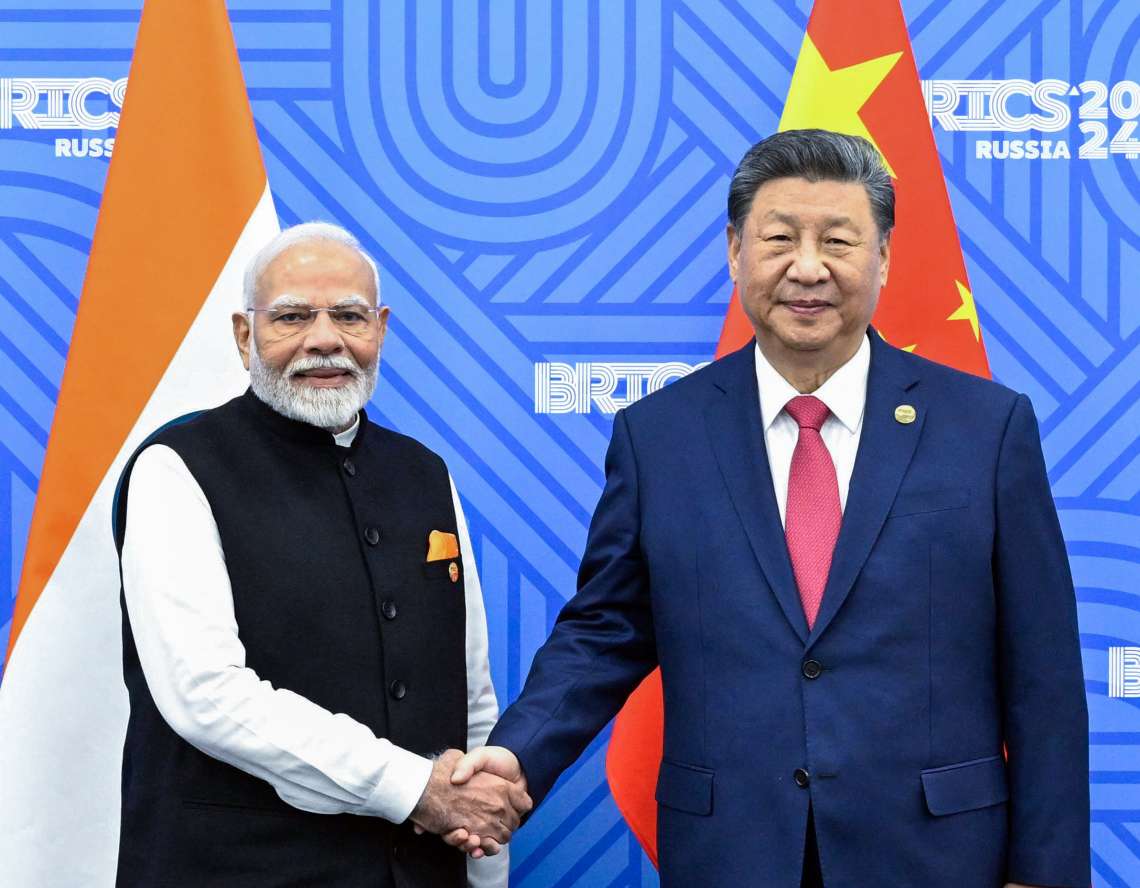

For Washington and Brussels, the optics could hardly be more troubling. India, long courted as a democratic counterweight to China, is clasping hands with both Xi and Putin, writes Kaliph Anaz

The West’s pressure campaign is beginning to unravel. In the northern Chinese port city of Tianjin, world leaders have gathered for what Beijing calls the most consequential Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in the bloc’s 24-year history. At its centre are three figures who now symbolise a shifting global order: Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The SCO’s weight is formidable. Its 10 full members — China, India, Russia, Pakistan, Iran, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan — together account for nearly 40 per cent of the world’s population and hold some of the planet’s largest energy reserves. The presence of two UN Security Council veto powers, China and Russia, gives the grouping a geopolitical heft that makes it more than a talking shop. It represents, in Beijing’s framing, the skeleton of a “multipolar world order” capable of pushing back against Western dominance.

For Washington and Brussels, the optics could hardly be more troubling. India, long courted as a democratic counterweight to China, is clasping hands with both Xi and Putin. Modi arrives in Tianjin on his first visit to China since 2018, fresh from securing a $68 billion Japanese investment pledge in Tokyo. But his real signal is to Washington: India will not be boxed in by US tariffs or by pressure to scale back Russian oil purchases. By stepping into Tianjin, Modi is showing that he has options beyond the Western orbit — and that he is willing to use them.

Putin, isolated under a web of Western sanctions, has seized the SCO stage to underline his pivot eastward. The Kremlin has already flagged bilateral meetings with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on Ukraine and with Iran’s President Masoud Pezeshkian on Tehran’s nuclear programme. Both conversations cut to the heart of Western anxieties. For Putin, the summit is an opportunity to demonstrate that Moscow is far from friendless — and that Russia’s global relevance is being sustained not through Western approval but through non-Western partnerships.

Xi, meanwhile, is casting China as a stabilising power in contrast to what Beijing denounces as U.S. “economic coercion.” For him, the SCO is a showcase: a reminder that while Washington tightens tariffs and sanctions, China is busy hosting leaders from across Asia, the Middle East and Eurasia under a banner of cooperation. The signal is that Beijing is not isolated, but central.

The SCO’s reach extends beyond its 10 members. Sixteen partner and observer states are also in Tianjin, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt and NATO member Turkey. Their participation highlights how the organisation is becoming a magnet for states that feel squeezed by, or at least uncomfortable with, the Western-led order. Even the United Nations has leaned in: Secretary-General António Guterres met Xi on the sidelines, urging reforms to the global financial system in a tacit nod to the frustrations many emerging economies share.

Still, few expect dramatic breakthroughs from the summit itself. India and Pakistan will share a stage for the first time since the recent Pahalgam terror attack and subsequent Indian military operation, but little movement is anticipated. Analysts see the event as more about theatre than substance — a stage where leaders can project images of defiance and partnership rather than ink binding agreements.

Yet theatre itself carries weight. Xi will aim to present China as indispensable, a steady hand amid turbulence. Putin will show himself unbowed, defiant in the face of isolation. Modi, perhaps most intriguingly, will project himself as the rare leader able to straddle divides: still engaging the United States and its allies while keeping doors open to Moscow and now Beijing. For India, that balancing act may prove risky — but it also elevates New Delhi as a swing player in the contest for global influence.

For the West, the image is deeply unsettling. As Trump’s trade war rattles Asian markets and European economies struggle to wean themselves off Russian energy, the spectacle of India linking arms with China and Russia delivers a sobering message: pressure alone is not fragmenting the non-Western world, it is instead pushing it closer together.

The summit concludes on Monday, after which many leaders will head to Beijing for a military parade marking 80 years since the end of World War II. That spectacle will be another reminder of how China uses history and ceremony to reinforce its claim to centrality in world affairs. For Washington and Brussels, the real lesson of Tianjin may lie less in speeches or communiqués than in the steady parade of countries marching, however cautiously, beyond Western control.