Historic buildings crumble amid builder mafia’s relentless pursuit … writes Dr Sakariya Kareem

Pakistan’s architectural and cultural legacy is facing an unprecedented crisis.

Across major cities and small towns alike, historic buildings—many of which are centuries old—are being reduced to rubble in the name of progress, commercial expansion, and unchecked real estate greed.

The relentless assault on the country’s heritage is not merely an issue of urban development; it is a systematic erasure of identity, history, and memory, often facilitated by a builder mafia that operates with impunity, frequently in collusion with local authorities.

From Karachi’s colonial-era structures to Lahore’s crumbling havelis and Peshawar’s centuries-old bazaars, the tale is disturbingly familiar: land values surge, heritage structures are suddenly declared “dangerous,” tenants are evicted or driven out, and the buildings are hastily torn down.

In their place rise concrete towers—anonymous, soulless, and profitable. The result is not development; it is desecration.

Forgotten architecture

In Karachi, the country’s largest city, the destruction is most visible and most jarring.

Once known for its charming blend of Art Deco, British Raj-era structures, and early 20th-century townhouses, Karachi today is a construction site of high-rise apartments and glass-faced commercial centres.

The city’s Sindh Cultural Heritage (Preservation) Act of 1994, which ostensibly protects over 1,200 heritage sites, has become a hollow legal shield.

Despite the law, dozens of registered heritage buildings have either been illegally altered or demolished outright.

The culprits are rarely held accountable. Builders, emboldened by their political and financial clout, continue their operations undeterred.

In many cases, heritage boards or municipal departments are complicit, turning a blind eye to unauthorised demolitions or rubber-stamping clearance certificates under dubious pretexts.

The incentive is simple: the land is more valuable than the building that sits on it.

A notable case involved the demolition of the historic Jufelhurst School, established in 1931, in Karachi’s Soldier Bazaar area.

Despite protests, media coverage, and a clear heritage status, bulldozers rolled in overnight.

When authorities were questioned, the explanation was characteristically vague: encroachments, safety concerns, redevelopment plans. The real reason was painfully evident—greed, shielded by indifference.

The vanishing soul

In Lahore, the cradle of Mughal and colonial heritage, the destruction is cloaked in the rhetoric of “beautification” and “revitalisation.”

While some conservation efforts exist—such as the Walled City of Lahore Authority’s (WCLA) work in select areas—the broader picture is one of alarming neglect and rapid commercialisation.

Heritage buildings are often gutted from the inside while their façades are preserved for optics.

Behind the scenes, hotel lobbies and shopping arcades replace courtyards, wooden staircases, and frescoed ceilings.

Lahore’s famed havelis, once alive with poetry, politics, and tradition, now lie in ruin or have been absorbed into commercial complexes.

Local residents, unable to afford upkeep or fend off developer pressure, either sell or are displaced.

The city’s skyline is being steadily transformed, not by design or planning, but by speculative real estate ventures that have no regard for history.

Moreover, the influence of the builder mafia in Punjab has grown significantly in recent years, often cloaked behind the facade of cooperative housing societies or politically backed urban renewal schemes.

These entities operate with legal dexterity, using vague zoning regulations and exploitative eviction tactics to clear land occupied by heritage structures.

Disintegration at the margins

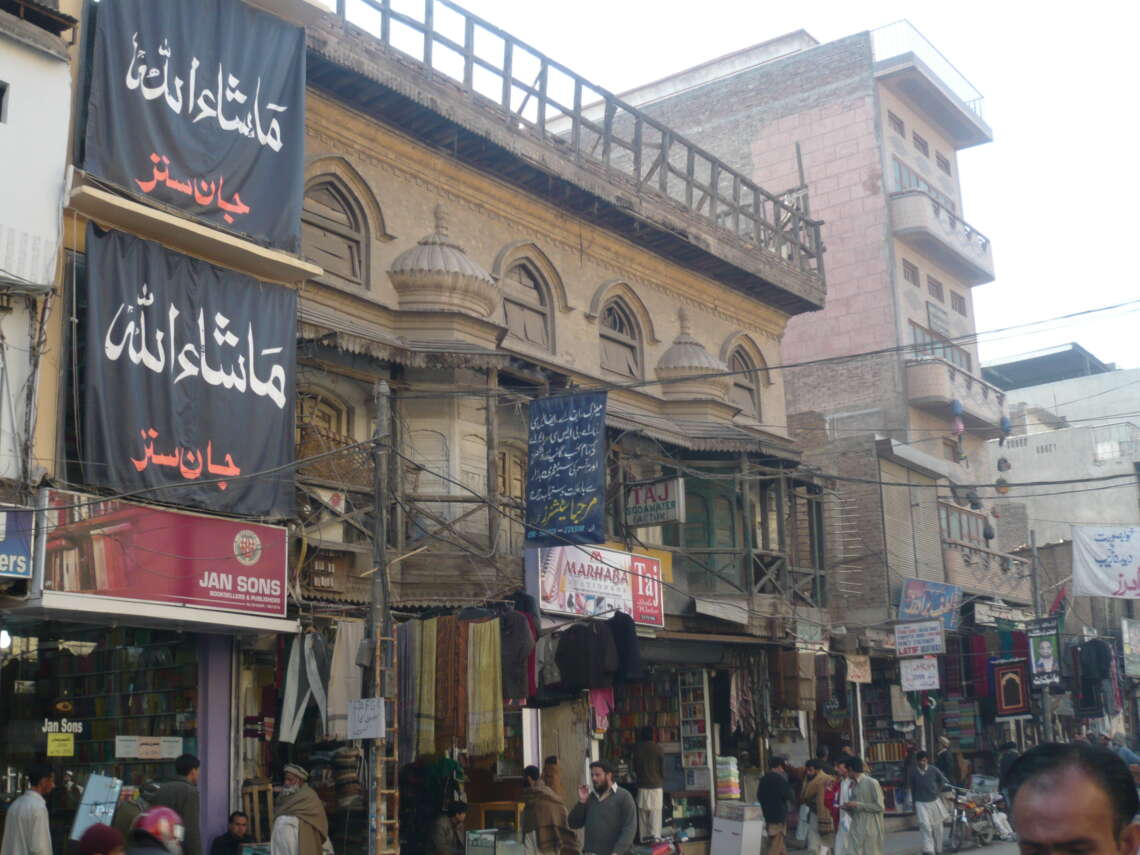

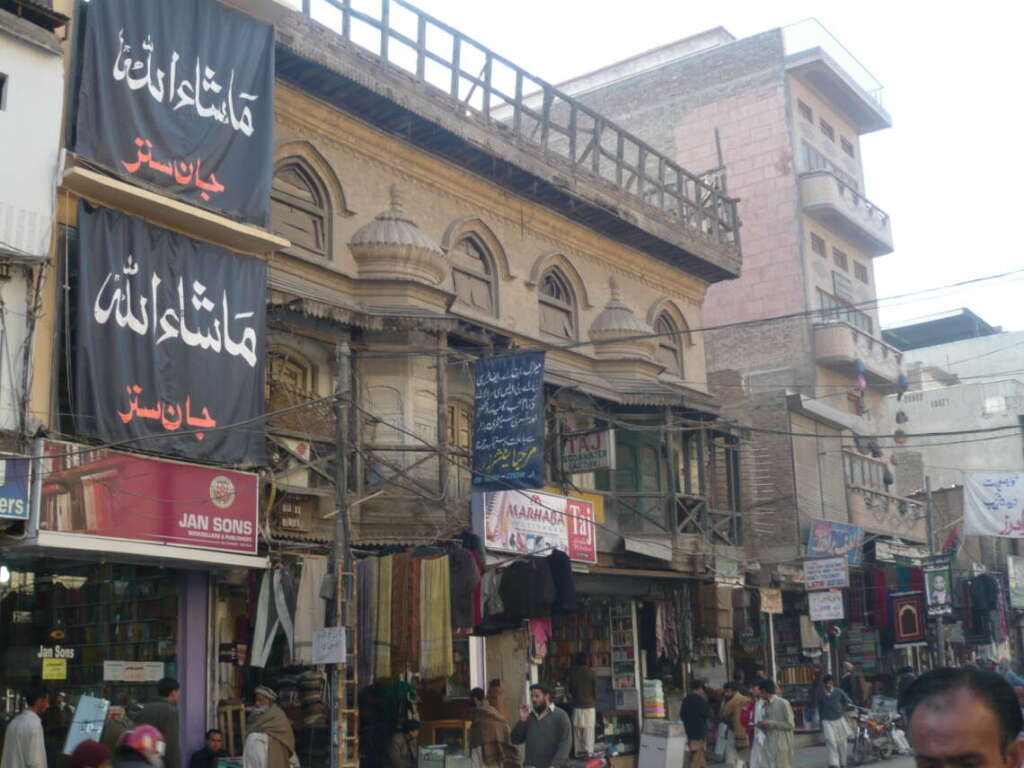

Peshawar, one of South Asia’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, is also falling victim to the tide of reckless construction.

The historic Qissa Khwani Bazaar, once the heart of storytelling and resistance movements, is now surrounded by a chaotic mix of concrete blocks, illegally modified shop fronts, and crumbling buildings.

Many homes dating back to the pre-Partition era have collapsed due to neglect, while others have been demolished under the guise of commercial necessity.

Meanwhile, in Balochistan, particularly in Quetta and Kalat, British-era buildings and ancient tribal structures are quietly disintegrating.

The absence of public awareness, government interest, or media attention makes these losses invisible.

Unlike Lahore or Karachi, where some resistance still exists, the heritage of Balochistan is vanishing in silence—forgotten and forsaken.

What makes this unfolding crisis even more tragic is the existence of institutions theoretically tasked with safeguarding these very sites.

Pakistan boasts several heritage laws, including provincial acts and constitutional provisions that mandate the protection of historical and cultural assets. Yet enforcement remains dismal.

The departments responsible for heritage preservation are often underfunded, understaffed, and politically marginalised.

Their recommendations carry little weight in the face of developer lobbying and political expediency.

In some cases, they are reduced to issuing press releases after demolitions, their voices drowned by the noise of jackhammers and excavators.

Pakistan’s courts, too, have failed to create consistent legal precedents that prioritise heritage over profit.

Even when stay orders are issued, builders find ways to bypass them, often demolishing overnight before authorities can respond. Fines, when imposed, are negligible compared to the profits at stake.

The destruction of heritage buildings is not just an architectural loss; it is a cultural and psychological wound.

These structures are vessels of memory, community, and identity.

They embody the syncretic histories of Pakistan — Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Christian, Zoroastrian, and others. Each haveli, shrine, or colonial mansion carries stories of migration, resistance, resilience, and coexistence.

When these are reduced to rubble, so too are the intangible threads that bind communities to their past.

Urban landscapes become sterile and indistinct, robbed of the richness that made them unique.

Children grow up without ever knowing the neighbourhoods their grandparents described. Tourists seeking heritage are met with malls. Citizens seeking pride in their urban identity are left only with glass towers and concrete sprawl.

The irony is bitter: a nation so eager to project cultural pride on the global stage through soft power—via cuisine, music, fashion—remains startlingly negligent toward the very physical spaces that embody its legacy.

The rise of the builder mafia in Pakistan is not just a story of real estate greed; it is a story of state failure, civic apathy, and cultural loss.

Every building lost is a chapter erased from the nation’s story. And yet, the bulldozers continue to move, carving profits from the ruins of the past.

Until this cycle is broken, Pakistan risks not only losing its heritage but also the very soul of its cities.