Experts called for action at a side event hosted by Global Human Rights Defence (GHRD) during the 54th session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, writes Marco Respinti

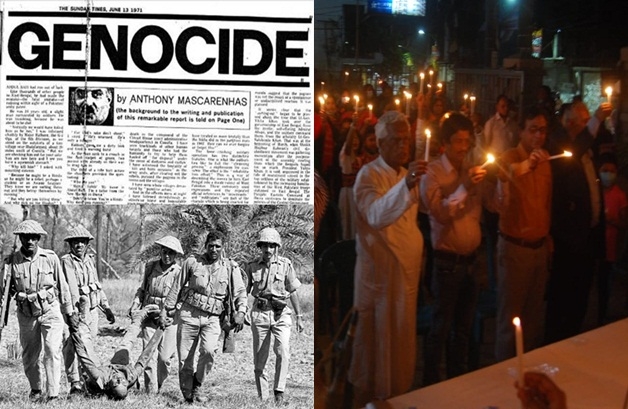

Undoubtedly, the massacre of Bangladeshi people perpetrated in 1971, during Muktijuddho, the Liberation War, by Pakistani armed forces’ “Operation Searchlight,” and their local allies of the Islamist Razakar militias, was a genocide. Also the authoritative Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention, named after the Polish jurist Rafael Lemkin (1900–1959), who in 1944 set the ground for the definition of that unique crime, recognized it. But while documents and plenty of evidence prove it, the specific legal reality of that slaughter has not received full international recognition yet.

Among others, Global Human Rights Defence (GHRD), an NGO with ECOSOC status based in The Hague, The Netherlands, took the case seriously. Recently, it released an important documentary, “What Happened? The Liberation of Bangladesh,” to raise the attention of the world. On the same line on October 5, 2023, it hosted a side event in the Palais de Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, during the 54th session of the UN Human Rights Council. The event was coordinated by GHRD Chairman, Sradhanand Sital, and Jessica Schwarz, Women’s Rights Researcher at GHRD. More than eighty participants were present in person while many others followed in streaming. Delegations came from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), Belgium, and the European Union (EU).

Harry van Bommel, a Dutch politician and human rights activist, illustrated the fact-finding mission to Bangladesh he led in May 2023, when he and his colleagues were able to interview survivors and hear direct testimonies. The author, with others, of a clarion call article in “Bitter Winter” on the subject, he testified that the vast evidence of such crimes can lead only to the conclusion that Bangladesh really suffered a true genocide. Such evidence, he added, will be soon taken to the EU and other international institutions, also to somewhat compensate what he described as the silent attitude of the world.

Shanchita Haque, Deputy Permanent Representative of Bangladesh to the UN in Geneva, citing international law and a well-known 1972 report of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) argued that legally those crimes fulfill the requirements of the 1948 “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” (established on the basis of the pioneering works by Lemkin) to be defined as a genocide. She also reminded that a 1973 act of the Jatiya Sangsad, the Parliament of Bangladesh, authorized the investigation and prosecution of those who had been responsible for all kind of crimes, genocide included, committed in 1971, leading to the establishment of two tribunals, the International Crimes Tribunal-1 in 2009 and the International Crimes Tribunal-2 functioning from 2012 to 2015, in the Old High Court Building of the Bangladeshi capital, Dhaka. These tribunals even sentenced to death some of the Bangladeshi collaborationists who operated alongside the Pakistani Army.

But another form of abuse, Haque underlined, was waged against the people of Bangladesh: the flagrant violations of their civil, cultural, and political rights, as well as the suppression of their religion and the Bengali language in an attempt to ethnically cleanse the region. Gender-based violence against women was sadly also a common practice.

Taking the floor at the GHRD event, Anthonie Holslag, lecturer at the Vrije Universiteit of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, expert in International Law and Genocide, and a participant in the May 2023 fact-finding mission led by van Bommel, offered an academic perspective on the matter. Aptly distinguishing between crimes against humanity and genocide, he stated that the discriminatory language and physical harm caused to Bengali property and people by aggressors in 1971 showed a clear contempt for their identity, which in turn revealed a clear intent to wipe out their whole community. Mentioning the case of Tutsis in Rwanda as an exemplary model, he focused on the concept of “otherness” by which Bangladeshi were “othered” in order to be alienated and ultimately removed. For him, there is then no contention regarding whether the series of crimes committed in 1971 can be considered a genocide.

In conclusion, Sital pointed at the three million casualties, over 200,000 raped women and around thirty million people displaced, both internally and externally, to ask the UN to officially recognize this genocide after more than half a century of oversight, making it a priority for its member states and NGOs. Significantly, he went even beyond this. “Experts tell us,” Sital commented, “there have been 37 incidents of genocide since 1945, but today, we focus on some that demand our immediate and universal attention: East Timor, Cambodia, Guatemala, Bosnia, Rwanda, Darfur, and more recently, the suffering of the Yazidi people at the hands of ISIS. These are painful reminders that ‘Never again’ must become more than just words. In 2023, we cannot afford to turn a blind eye to the urgent crises unfolding before us. The genocide against the Yazidi community, the ongoing persecution of Armenians, the plight of minorities in Pakistan, the suffering of the Uyghur population, the relentless conflict in Yemen, and the struggles of the people of Ukraine demand our unwavering attention and action.”

On 11 March 2017, the Jatiya Sangsad unanimously passed a resolution designating March 25 as a Genocide Remembrance Day. This is a date that the UN could also designate as one of its days of observance and dedicate to the tragedy of Bangladesh, twinning it to its International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide and of the Prevention of this Crime observed on December 9.

ALSO READ: Bangladesh: From a Basket Case of Woes to an Economic Powerhouse