The most recent subtle initiative Indonesia has taken is to invite officials in charge of maritime security from five other countries in ASEAN to meet to discuss how to respond to China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea….writes Baladas Ghoshal

China has formally opened another front in its bellicosity in the South China Sea, and practically forcing Jakarta to accept a dispute in the Natunas, where there is none, as the area concerned is within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Indonesia as per the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Beijing claims that its “nine-dash” line, an artificial boundary invented by the CCP (Communist Party of China) that covers most of the South China Sea, giving it ownership of this entire maritime area extending to the EEZ of Indonesia in the Natuna Islands. The EEZ is an area extending up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline of a country. While other countries have a right of innocent passage in such territory, a country has special rights regarding exploration and use of maritime resources in its EEZ, to the exclusion of other powers. Jakarta has always stood up to China bullying her in the EEZ without declaring it loudly.

China has repeatedly told Indonesia to halt an oil and natural gas development project in the South China Sea, claiming infringement on its territorial waters. But in early December last year, it officially communicated to the Indonesian government to stop appraisal drilling at Harbour Energy’s (LON:HBR) Tuna Block offshore Indonesia in maritime territory that both nations view as their own during a months-long standoff in the South China Sea, reported Reuters. The unprecedented demand raised tensions over natural resources between China and Indonesia in a volatile area of global strategic and economic importance. China not only objected to the drilling operations, but had also sent coast guard vessels into the area to mount pressure on Indonesia. Jakarta has not openly disclosed about China’s protests, as that would amount to an admission of a dispute in the area. Even while it does not acknowledge the existence of a dispute, Indonesia in May 2020 sent the United Nations a letter rejecting Beijing’s historical claims in the sea indicated by its nine-dash like maps.. China, in turn, sent a counter reply to the UN, maintaining its claims in the South China Sea while seeking a solution through negotiations, which Jakarta flatly rejected.

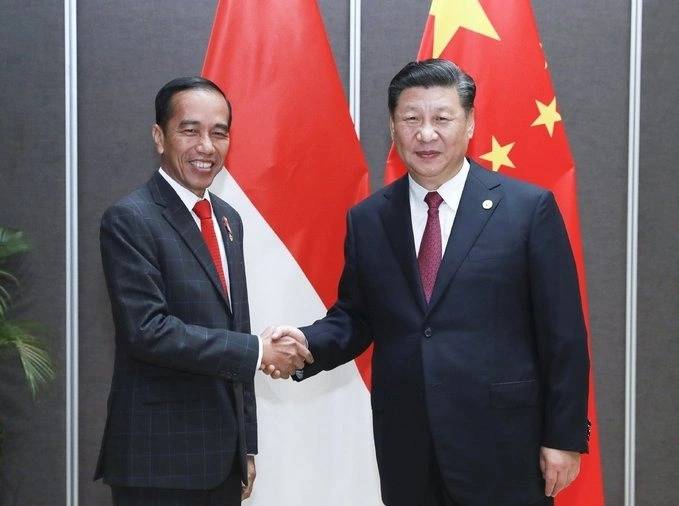

While not inclined to make the spat with China public, Indonesian President Joko Widodo has pursued Jakarta’s traditional diplomatic approach of being equidistant from both the United States and China. Like most other ASEAN countries, Indonesia doesn’t want to take sides between the two rival powers despite all the Chinese bullying. And he adopted a clever strategy of roping in Britain and Russia to deal with the Chinese pressure. Jakarta sought the support of a consortium of Britain’s Harbour Energy and Russian state oil company Zarubezhneft to lay a pipeline across the North Natuna Sea to connect with Vietnam’s offshore network. The two companies have already announced that they have found a modest gross gas resource of 600 billion cubic feet after drilling of two appraisal wells in the Tuna block, about 10 km from Indonesia’s EEZ. Despite Beijing’s objections, the drilling continued for six months and was completed last November with Indonesia’s Bakamla (Badan Keamaanan Laut Repulik Indonesia- Indonesian Maritime Security Agency)- claiming success in their ventures, which some analysts called it “a grand �victory’ over the Chinese.”

Beijing’s bellicosity in the South China

China equally doesn’t let Vietnam drill oil and gas in its own EEZ, which forced Hanoi to seek Tokyo’s support. Similarly, China doesn’t let the Philippines drill oil in its own waters either, which ultimately forced Manila to start drilling in open defiance to China. Not only that, Beijing imposes annual summer fishing bans in the South China Sea in an attempt to deprive other legitimate countries from fishing in their own EEZ. Both Malaysia and the Philippines too, face an aggressive Beijing in their South China Sea possessions. China already controls the Scarborough Shoal – a disputed feature in the South China Sea, claimed by both Beijing and Manila. Presently, Chinese maritime militias are also eyeing Whitsun Reef, a geographical feature in Filipino waters, which is also being claimed by China. Malaysia, on the other hand, is itself a victim of Chinese bullying. Chinese coastguard ships harass Malaysian oil and gas vessels operating in their own waters. China claims Malaysian territory also and forbids it to drill there.

Signs of Unity among the Claimant States

Brunei, a tiny Sultanate, where China has invested extensively, was naturally passive for a long time in its response towards Beijing denying the country to drill in its own EEZ. But last year, Brunei was appointed as the ASEAN chair and was no longer passive and it quietly showed the ability to mobilise claimant states of ASEAN as well as Indonesia, to express concern about China’s aggressive behaviour over the South China Sea disputes. This happened despite China’s attempts to woo Brunei through vaccine diplomacy sending a batch of Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccines in a donation to which its Second Minister of foreign affairs Haji Erywan thanked the former. In January, a Chinese state-owned company Guangxi Beibu Gulf International Port Group had also signed a deal to redevelop and manage a fisheries port in Brunei. But the tiny Kingdom decided to cooperate with other South China Sea disputants who wanted to tackle Beijing’s assertiveness in the hotly contested region. While China is trying to pull Brunei to its side, the latter, it seems, has made up its mind to stick with fellow South China Sea disputants within the regional bloc.

ALSO READ: Students stage anti-China protest in Indonesia

Singapore, which is neither a claimant state on the South China Sea, nor has any disputes with any ASEAN members, is also increasingly becoming active on finding a way to manage the conflict. Recent agreements for cooperation in oil exploration and maritime security sectors suggest that some ASEAN members are ready to forgo their own petty differences and take on the main challenge, China. Plans for a maritime accord between Malaysia and Vietnam, for instance, indicate how the ASEAN neighbours are ready to come closer to each other in face of growing Chinese revisionism. However, minor the shift is, it is the beginning of a semblance of unity among some ASEAN members in the face of China’s belligerence and their own existential crisis.

Indonesia dares China

The most recent subtle initiative Indonesia has taken is to invite officials in charge of maritime security from five other countries in ASEAN to meet early next year to discuss how to respond to China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea. Head of Bakamla, Vice Adm. Aan Kurnia, was quoted in the Indonesian media as telling reporters that he had invited his counterparts from Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam to a meeting in February 2022 to “share experiences and foster brotherhood” among the countries facing similar challenges posed by China. Maritime agencies from the six countries took part in an ASEAN Coast Guard Forum last October, signalling willingness to cooperate. The Jakarta Post quoted Aan as saying that it is important “to present a coordinated approach” in matters related to the South China Sea, and “how to respond in the field when we face the same �disturbance’.” The vice admiral did not mention China by name.

A meeting similar to the ASEAN Coast Guard forum would be a “great opportunity for ASEAN coast guards and maritime law enforcement agencies to talk and cooperate with each other,” Satya Pratama, a senior Indonesian government official and a former Bakamla captain was quoted to have said. “It is also a good idea for Indonesia [through Bakamla] to explain Indonesia’s intention so that others can understand and follow suit,” he said.

ALSO READ: Dragon is watching: China intensifies surveillance

“Coast guards in Southeast Asia have a bad history of cooperation – they see each other as their primary challenges, even worse than the navies, which have learned to cooperate amid competition,” to quote Thomas Daniel, a senior fellow at Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS).. This is reflected in ASEAN’s attempt to negotiate a Code of Conduct (COC) to regulate maritime activities there, with some nations like the current ASEAN chair Cambodia reluctant to criticize Beijing. This also finds expression in the comment by the Filipino foreign secretary Teodore Locsin Jr. who spoke of those difficulties earlier last month when he addressed a meeting between foreign ministers from ASEAN and Group of Seven (G7) developed countries. He said that as ASEAN countries and China struggle to agree on the South China Sea issues, “recent incidents and the heightened tension � remain a serious concern.” “These worrying developments underscore the urgency and importance of the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea � But negotiations for the COC, even on our watch, went nowhere,” Locsin said. Antonio Carpio, a former justice of the Philippine Supreme Court, had his own suggestion that five ASEAN coastal states – the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei, plus Indonesia – should form a coalition “to oppose China’s hegemony and bullying”

Challenges to Unity remain

Forging unity among the five ASEAN states is not going to be an easy task, as there are longstanding trust issue between them, as well as fear of retaliation by China. In the meantime, however, the Vietnam Coast Guard and the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency signed a memorandum of understanding last month on cooperation in strengthening maritime security and safety between the two forces. But overlapping maritime claims have been an irritant in Vietnam-Indonesia bilateral relations for decades. The two countries frequently clash over the issue of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. In 2019, for example, Indonesia seized and destroyed 38 Vietnamese vessels for illegal fishing. A similar situation is seen between Vietnam and the Philippines, as well as between Indonesia and Malaysia. Yet the very attempt by Indonesia to create some understanding between the coast guards of the five countries signals a resolve on their part to display their unity vis-�-vis the Chinese bully. Whether the attempt to forge unity succeeds or not, it surely heralds a shift in the ASEAN way of doing things from consensus principle to pragmatic approach to deal with China challenge.

Indonesia bolstering its own defences

Meanwhile, on its own,Indonesia is preparing herself for any eventuality and looks to bolster its defences in and around Natuna, suspecting that China is exploring opportunities to seize effective control of the islands. The Indonesian military is lengthening an air base runway so that additional planes can be deployed, together with the construction of a submarine base as well. Local fishing vessels act as eyes and ears, take part in an early warning system on the lookout for approaching Chinese ships. With the USA, Jakarta is building a joint training facility for coast guard personnel near Natuna. The two nations held their biggest joint military exercise to date this August, spanning three locations in Indonesia. The drills simulated island defences.

Indonesia could be the next buyer of BrahMos after the Philippines

To build its defence capacities and capabilities Indonesia also has growing defence cooperation with Japan, Australia and India. New Delhi has already finalized a deal with the Filipinos for supply of Brah-Mos supersonic missile systems, jointly produced by India and Russia, amid China’s aggressive territorial claims in the South China Sea region. BrahMos will upload substantial confirmed capacity to the Philippines’ coastal defences, and it compares favourably with the anti-ship missiles in carrier with different navies. It is some distance quicker than the U.S. Army’s Tomahawk or the Chinese language PLA Army’s YJ-18.

India is exploring the possibility of selling the BrahMos cruise missile to Indonesia, and a team from the Indo-Russian joint venture that makes the weapon system visited a state-run shipyard in Surabaya last year to assess the fitting of the missile on Indonesian warships, Besides the BrahMos, India has offered to supply coastal defence radars and marine grade steel to Indonesia and to service the Russian-made Su-30 combat jets flown by the Indonesian air force as part of efforts to deepen bilateral defence and military cooperation.

With a commanding maritime strategic location and ample attributes of developing its national power, Indonesia could well become the spearhead within the ASEAN to checkmate China’s expansionist drive in the South China Sea.

(The content is being carried under an arrangement with indianarrative.com)