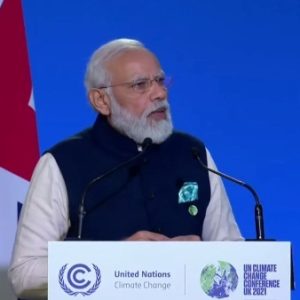

Acutely aware of the shifting balance of power and changes in the “big picture” it would not be unexpected if Wang, during his visit shows a change of tack on India’s concerns. This would be in the hope of persuading New Delhi, a swing player, to stand steadfast and not bandwagon with the West during the still unfolding crisis in Ukraine, a report by Atul Aneja

Chinese foreign minister and state councillor, Wang Yi is arriving in India on Thursday at a time when the “big picture” of global alignments is changing profoundly after Russia’s attack on Ukraine. In response to the Russian move, the US-led West has taken a strategic decision to ostracize Moscow from the international system.

The Chinese are clear about defining their response to the deep polarisation that has emerged between US and Russia. If pushed to a wall, the Chinese will back Russia and ensure that resource rich Eurasia remains united vis-à-vis the Atlantic Alliance, notwithstanding the dangerous consequences it would entail ranging from a new Cold War to World War 3, where thermonuclear weapons may be deployed.

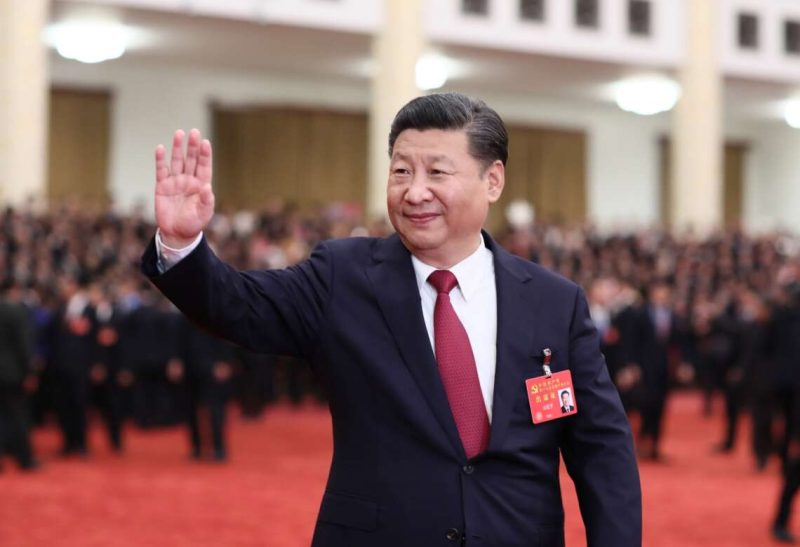

So why is China so intent to back Russia, even when US President Joe Biden is trying to woo his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in order to isolate Moscow? Afterall, a convergence of interests with Washington would fulfil the aspirations of an influential section of the Chinese elite which has been sold on the idea of establishing a G-2, comprising Beijing and Washington on the apex of the global system.

The roots of forging an impregnable pan-Eurasian bond by Russia and China go back to the heady days of the Arab Spring. In October 2011, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was killed under the cover of a UN mandated no-fly zone, which came into existence only when China and Russia, wanting to avoid an open confrontation with the west, chose to abstain from a series of UN Security Council resolutions.

Gaddafi’s murder was a turning point in Russia and China’s strategic appreciation of western intent. Both fully grasped that Arab Spring, colour revolutions, crusades for democracy and human rights were cover for hard geopolitics–of reinforcing the might of a US-led unipolar world through serial regime changes.

In fact, the process of toppling proud sovereign states with the purpose of hegemonising the global system began in the mid-nineties, with the bombing and breakup of former Yugoslavia. It was in that campaign mounted by the Clinton administration that soft power tools including non-violent street protests, training to withstand tear gas and rubber bullet attacks, and unleashing of a brutal information war though powerful mainstream and social media were honed and deployed.

Based on the valuable experience of the Balkans, a combination of hard and soft power was then seamlessly imposed in West Asia and North Africa. After 9/11 the Global War on Terror, supplemented human rights to fortify the moral high ground for fostering regime change. In West Asia it started in 2003 with the toppling of Saddam Hussein on contrived assumptions and ended with the brutal assassination of Gaddafi by NATO-backed radical Islamists, and the collapse of Libya into a failed state.

With Gaddafi’s death as a turning point, both the Chinese and the Russians, instead of abstaining, decided to exercise their veto at the UNSC to any moves by the West to advance regime change. Thus, the two countries worked together to ensure that the Syrian government led by Bashar Al Assad, which was on the brink, did not collapse. This was a turning point.

There was cold geopolitical logic to prevent the fall of Assad. Both Russia and China concluded that Syria in the Levant would be their first defence line. Iran would be the second, for both Moscow and Beijing feared that if Syria fell to the regime-change crusade, Iran would be next in the firing line. And if Iran fell, then the Eurasian heartland pillared by Russia and China would be fully exposed. Chinese pundits were well aware that for existential reasons, Russia and China had to hang together for if any of them fell to regime change, the next would be in the cross-hairs of a rampaging west.

Since then, Beijing’s strategic calculus is clear. Far from being seduced by the promise of a G-2, the Chinese know that such a move would completely isolate Russia, which would then be primed up for regime change. In turn it would open the floodgates for China to be subjected to a similar fate.

Acutely aware of the shifting balance of power and changes in the “big picture” it would not be unexpected if Wang, during his visit shows a change of tack on India’s concerns. This would be in the hope of persuading New Delhi, a swing player, to stand steadfast and not bandwagon with the West during the still unfolding crisis in Ukraine.

But the Chinese must realise that any shift in India’s stance, within the parameters of India Strategic Autonomy, can follow only after the status quo ante disturbed by Beijing through its incursion in May 2020 in eastern Ladakh is fully and unambiguously restored. Only then can an opening be created for better bilateral relations and a more robust Indian participation as a fellow emerging economy in the BRICS, whose summit China will host later this year.