She also noted that “as the climate heats up, it is likely that swathes of land will be submerged, water-related extremes will re-shape industry and famine will revisit the country.” (The first signs of this, in fact, are already visible.)…writes Vishnu Makhijani.

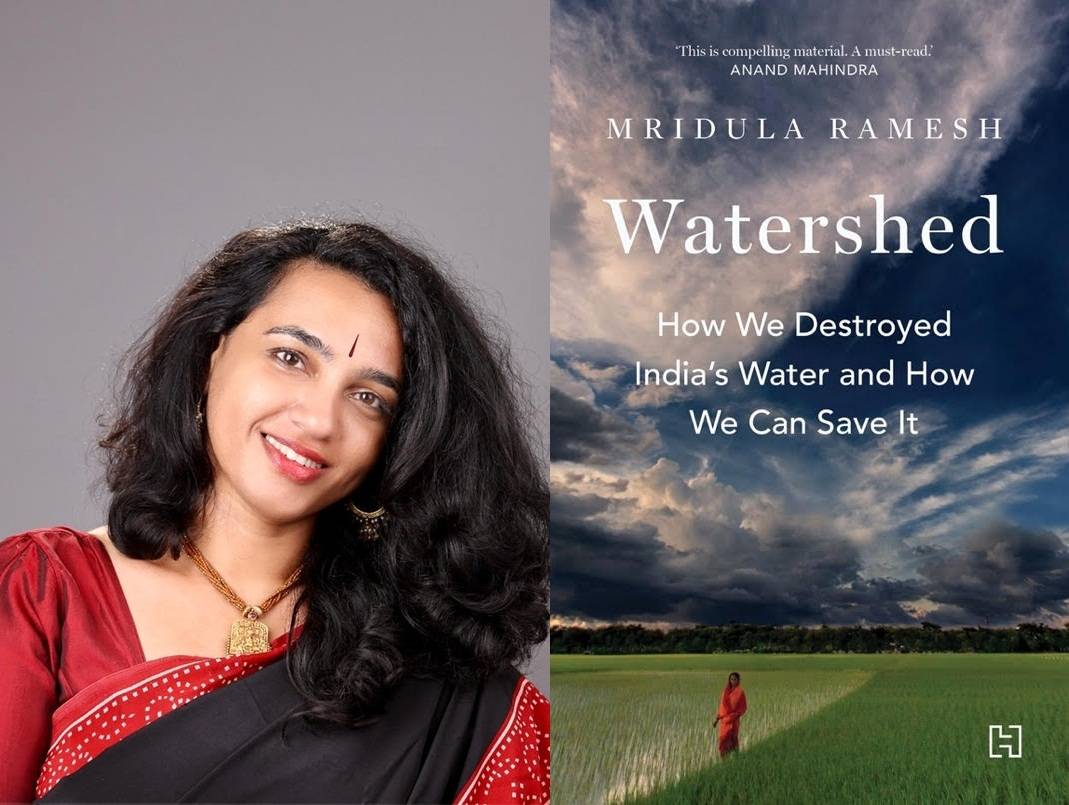

Mridula Ramesh, a leading clean-tech angel investor with a portfolio of over 15 startups and who is involved in multiple initiatives to build climate entrepreneurship, ran out of water at her Madurai home in 2013.

In trying to find out why that happened and what could be done about it, her first book, “The Climate Solution” and entry into the world of climate happened — only to realise that people speaking about climate change speak almost exclusively of carbon, while the climate itself speaks in the language of water.

“For India, arguably one of the most vulnerable countries to the changing climate, water needs its share of the conversation,” and her new book, “Watershed” (Hachette India), “is an effort to correct that imbalance” because “we have crossed certain climate thresholds, and need to address water to lessen the pain that Indians are feeling in this changed climate”, Mridula told.

More worrisome, the changing climate and water cycle “is highlighting inequalities — such as those between rich and poor within a given city and between the developed and developing world. Storms, flooding and drought affect the poor more than the rich,” she added.

Moreover, looking at this through a climate justice angle, “we find that adaptation (a large part of which is managing water) is getting a far less conversation-share and lower share of financing than mitigation, even though developing countries have contributed far less to the cumulative GHG emissions that have caused this global warming. This lower priority only serves to increase existing inequalities,” Mridula explained.

She also noted that “as the climate heats up, it is likely that swathes of land will be submerged, water-related extremes will re-shape industry and famine will revisit the country.” (The first signs of this, in fact, are already visible.)

“Sea-level rise and stronger storms and stronger storm surges will result in parts of the country being underwater for at least some time each year in the future. Many industries came up in the belief that water is endless and cheap — climate change is challenging both of those beliefs. For example, sectors like thermal power plants in dry regions may find the going far less profitable, and may need to relocate or shutdown.

“On famine, we have gone from a nation of 220 million eating largely millets to a nation of 1.3 billion eating rice and wheat. The price for this transformation has been paid largely from the groundwater reserved of the dry northwest. In 2019, a state committee had opined that Punjab may run out of groundwater in 20-25 years. What will happen if an El Nino hits after that? That’s what the plausible fictional scenario in Chapter 24 tries to portray � what can happen if all these come to pass in the near future,” Mridula cautioned.

To this end, the book provides a five-point checklist of action:

Acknowledge water — don’t take it for granted and see how India’s water is special. Acknowledge that we are the best keepers of our water resilience. Act with data and act now — begin by preparing a water balance sheet — where is it coming from and where is it going. Version 1.0 of this may not be perfect, but try every day to go a little further. The same holds true for a person, a community, a factory, a city, a state or a country.

Protect the forces that soothe India’s volatile and variable waters — this includes forests, tanks and sewage treatment. In doing so, keep in mind the importance of cash flow — something may be very valuable and provide a great water-smoothening service, but if it does not generate cash flow, it becomes vulnerable in our economic world.

Customers should recognise that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Ask your favourite brands to be conscious of their carbon/waste/water footprint, and ensure their entire supply chain is fairly compensated for respecting the environment.

Let us recognise the power of decentralised policy — water pricing at the level of a city, mandating distributed farmgate storage in a district or sensitising bulk generators of waste/sewage, tank tourism — can generate a wave of innovation that can bring the jobs India needs while building climate resilience.

We really are close to the abyss, and yet, most of our voters appear not to vote on managing our shared resources. This needs to change if we want meaningful policy action.

Considerable research has gone into the book, with the studies conducted by the Madurai-based Sundaram Climate Institute forming one of its core pillars.

“We have spoken to over 2,000 households on their waste and water realities apart from studying the communities and impact of 100 tanks. Then there was the historical research — many of which involved interviews, site visits and perusal of primary sources such as letters or writings of colonial officials. Then there was the peer-reviewed literature from archaeologists, geologists, chemists, hydrologists, climatologists, medical doctors, and historians,” Mridula elaborated.

There were extensive interviews and conversations with a varied spectrum of people, from India’s ‘Water Man’ Rajendra Singh, to the many startups trying to build water resilience, to scientists, business people, activists, bureaucrats and politicians. And finally the investment process in startups.

How does India compare with the rest of the world � with the US, Africa, and Europe?

“In terms of climate and water vulnerabilities, India ranks high — very high — because of its population, its relative financial position, the large share of rainfed farms in agriculture and its long coastline. Also important to note is that the Indian Ocean has warmed faster than the other oceans in the world, leading to more powerful storms,” Mridula said.

Speaking about her experience with her net-zero-waste home and how this can be replicated at the micro and macro levels, she said: “Before we did anything we collected data, what we wasted, who, why, how. Over time, patterns emerged and we began seeing what the biggest areas of waste were — so we brought the amount of ‘generated waste’ down.”

“Second, we began to see how much of the ‘waste’ we could reuse — that is re-imagination, how to see ‘waste’ as a ‘resource’ — that was the killer step. We make compost and biogas, which keeps the garden healthy and the costs down. We also bring in waste from outside — flower waste and cow dung — to help with the compost and biogas.

“We have had our successes and failures, but what has kept us going is the focus on data, and emphasis on making any action as easy to follow as possible,” Mriduala concluded.