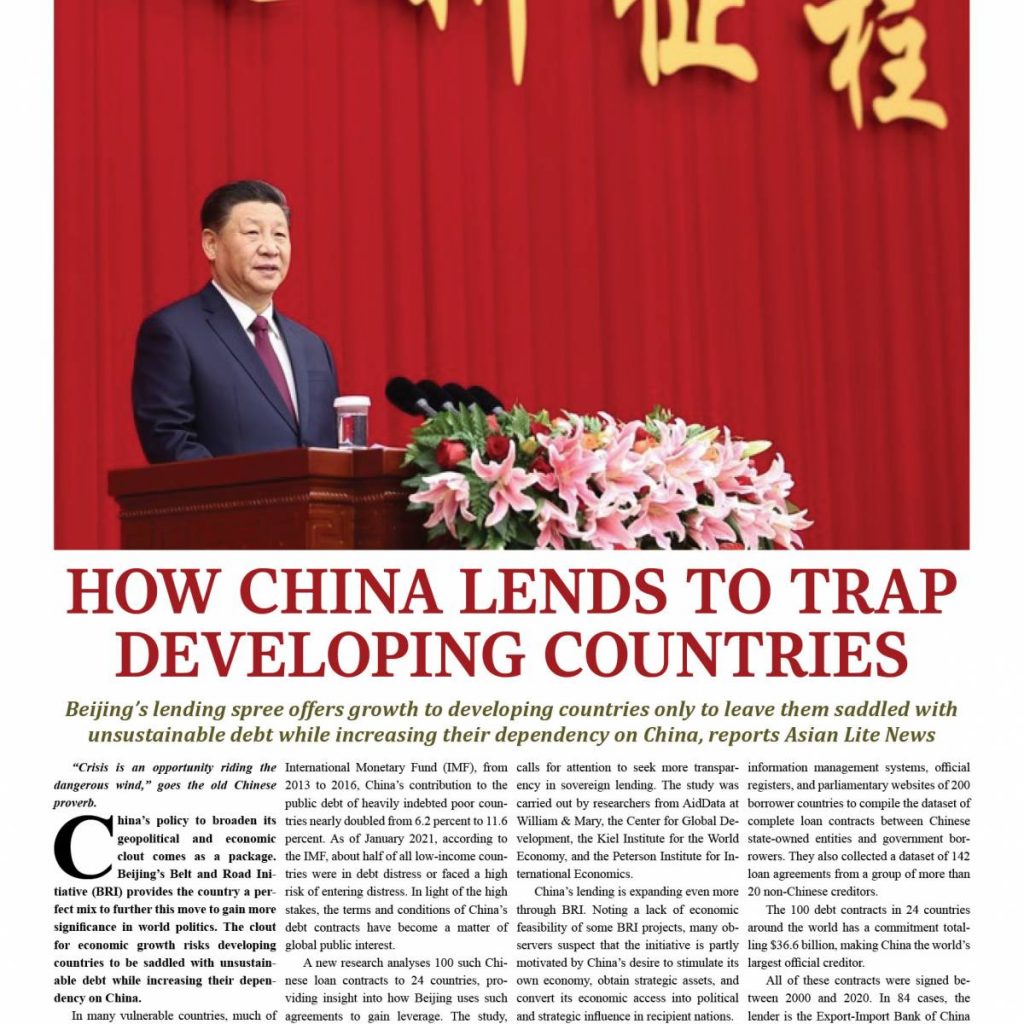

Beijing’s lending spree offers growth to developing countries only to leave them saddled with unsustainable debt while increasing their dependency on China, reports Asian Lite News

“Crisis is an opportunity riding the dangerous wind,” goes the old Chinese proverb.

China’s policy to broaden its geopolitical and economic clout comes as a package. Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provides the country a perfect mix to further this move to gain more significance in world politics. The clout for economic growth risks developing countries to be saddled with unsustainable debt while increasing their dependency on China.

In many vulnerable countries, much of the burdensome debt is owed to a single source: China. According to a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), from 2013 to 2016, China’s contribution to the public debt of heavily indebted poor countries nearly doubled from 6.2 percent to 11.6 percent. As of January 2021, according to the IMF, about half of all low-income countries were in debt distress or faced a high risk of entering distress. In light of the high stakes, the terms and conditions of China’s debt contracts have become a matter of global public interest.

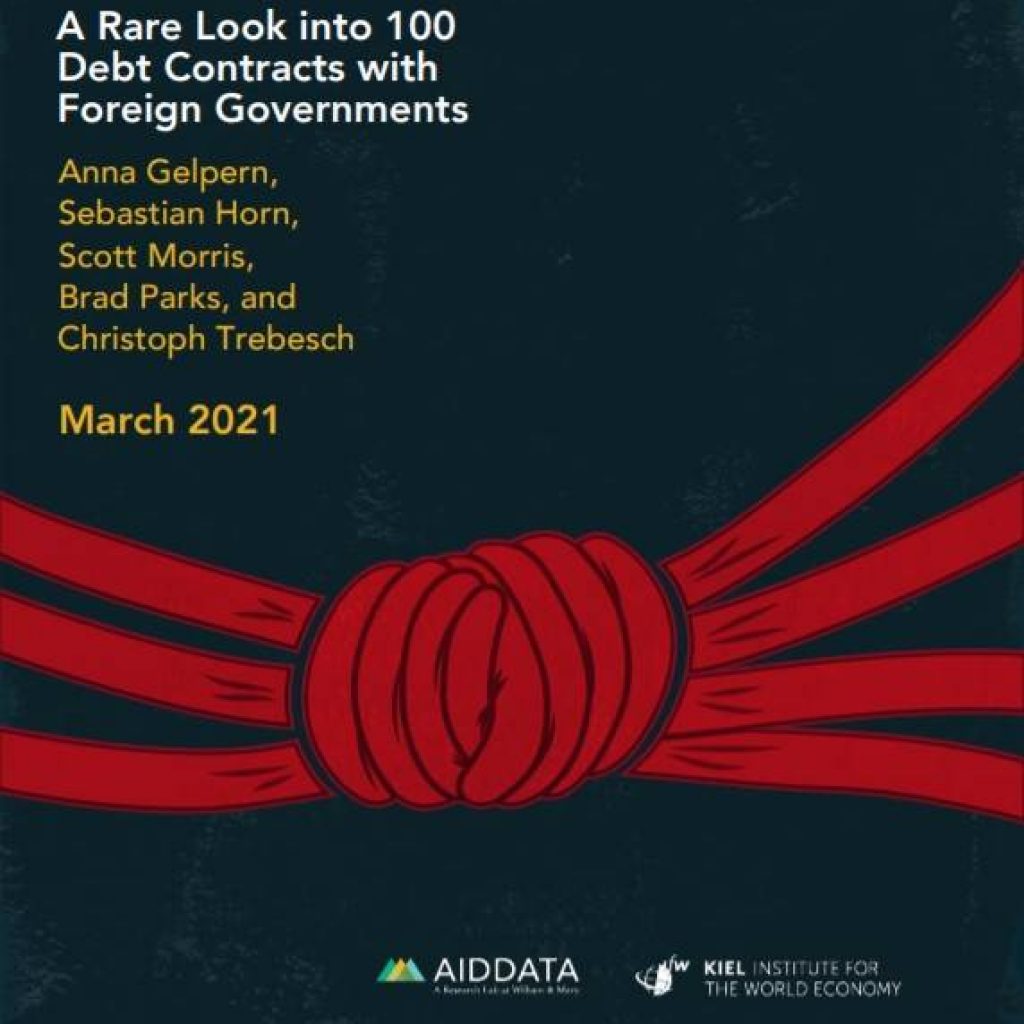

A new research analyses 100 such Chinese loan contracts to 24 countries, providing insight into how Beijing uses such agreements to gain leverage. The study, ‘How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments’ calls for attention to seek more transparency in sovereign lending. The study was carried out by researchers from AidData at William & Mary, the Center for Global Development, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, and the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

China’s lending is expanding even more through BRI. Noting a lack of economic feasibility of some BRI projects, many observers suspect that the initiative is partly motivated by China’s desire to stimulate its own economy, obtain strategic assets, and convert its economic access into political and strategic influence in recipient nations.

The study put together by 100 researchers took 36 months to comb through debt information management systems, official registers, and parliamentary websites of 200 borrower countries to compile the dataset of complete loan contracts between Chinese state-owned entities and government borrowers. They also collected a dataset of 142 loan agreements from a group of more than 20 non-Chinese creditors.

Also read:China warns US on global affairs

The 100 debt contracts in 24 countries around the world has a commitment totalling $36.6 billion, making China the world’s largest official creditor.

All of these contracts were signed between 2000 and 2020. In 84 cases, the lender is the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank) or China Development Bank (CDB).

Many of the contracts contain or refer to borrowers’ promises not to disclose their terms—or, in some cases, even the fact of the contract’s existence.

“Chinese lenders behave a lot like commercial lenders: muscular, commercially savvy lenders who want to be paid on time and with interest,” and the contracts are designed accordingly, said Brad Parks, executive director of AidData, which led the data gathering process.

How China’s loans work

The loan agreements made as part of BRI are written to position China as a “preferred creditor” that could seek repayment first in the event of a problem or default.

This is done through two primary ways: by requiring borrowers to create separate escrow accounts with cash balance requirements that China can seize in case of default. Another clause requires countries to exempt Chinese loans from restructuring efforts with other lenders.

These clauses are referred to as “no Paris Club” clauses. Basically referring to the informal group of official creditors that coordinate solutions for debtor countries with payment difficulties.

According to Sebastian Horn, an economist at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, another key finding of the study is that “Most Chinese loan contracts contain ‘No Paris Club’ clauses, which prohibit countries from restructuring Chinese loans on equal terms and in coordination with other creditors.” This approach to foreign lending effectively gives Beijing sole discretion to decide if, when, and how it will grant debt relief. Christoph Trebesch, also of the Kiel Institute, adds that “China’s practices complicate debt relief efforts in countries that are in financial distress due to the Covid-19 pandemic or other factors.”

Chinese contracts give lenders considerable discretion to cancel loans and/or demand full repayment ahead of schedule. Such terms give lenders an opening to project policy influence over the sovereign borrower, and effectively limit the borrower’s policy space to cancel a Chinese loan or to issue new environmental regulations.

Also read:China administers over 100mn jabs

Another point of leverage is that China often includes “cross-default” or “cross-cancellation” provisions that in essence tie various loans to one another. These clauses make it harder for a borrower to walk away from a project and give Chinese institutions bargaining power and policy influence, according to the study.

Deep implications

In such a scenario, the economic benefits of China’s debt-driven projects to recipient nations’ populations are an afterthought. And the lack of transparency in China’s lending obscures its risks to recipient countries, many of which are already vulnerable to or are suffering from financial or fiscal distress. But concealing risks does not eliminate their consequences, and when cash-strapped developing countries fail to pay back the loans for multibillion-dollar projects, it can result in a loss of strategic assets, major hurdles to economic development, and a loss of sovereignty.

For example, unable to repay China for a loan used to build a new port in the city of Hambantota, in 2017 Sri Lanka signed over to China a 99-year lease for its use, potentially as a strategic base for China’s navy.

In Djibouti, public debt has risen to roughly 80 percent of the country’s GDP (and China owns the lion’s share), placing the country at high risk of debt distress. That China’s first and only overseas military base is located in Djibouti is a consequence, not a coincidence.

Elsewhere in Africa, Burundi, Chad, Mozambique, and Zambia are all either in debt distress or at high risk of it, a situation China’s predatory lending practices are exacerbating.

In Argentina, where a $2 billion China Development Bank loan for a railway project had a cross-cancellation clause tied to a $4.7 billion loan from Chinese banks for a hydroelectric dam project. When a new presidential administration came in and tried to cancel the dam project on environmental grounds, the China Development Bank threatened to cancel the railway project loan. Argentina’s government reversed its decision.

Brad Parks, AidData’s Executive Director and a co-author of the report, says that “by shielding their contractual arrangements from public scrutiny, Chinese state-owned banks have made it difficult for other lenders to know if they are positioning themselves at the front of the repayment line.”

Hidden debts to China have also put developing countries—with insufficient foreign currency to repay all of their outstanding obligations to foreign creditors—in an equally challenging position. According to Parks, “non-Chinese creditors are increasingly reluctant to renegotiate repayment terms until they know more about China’s claims.”

The authors of How China Lends warn that restrictions on debt transparency make it difficult for citizens in borrower countries and creditor countries to hold their governments accountable, and call for public debt to be made public.