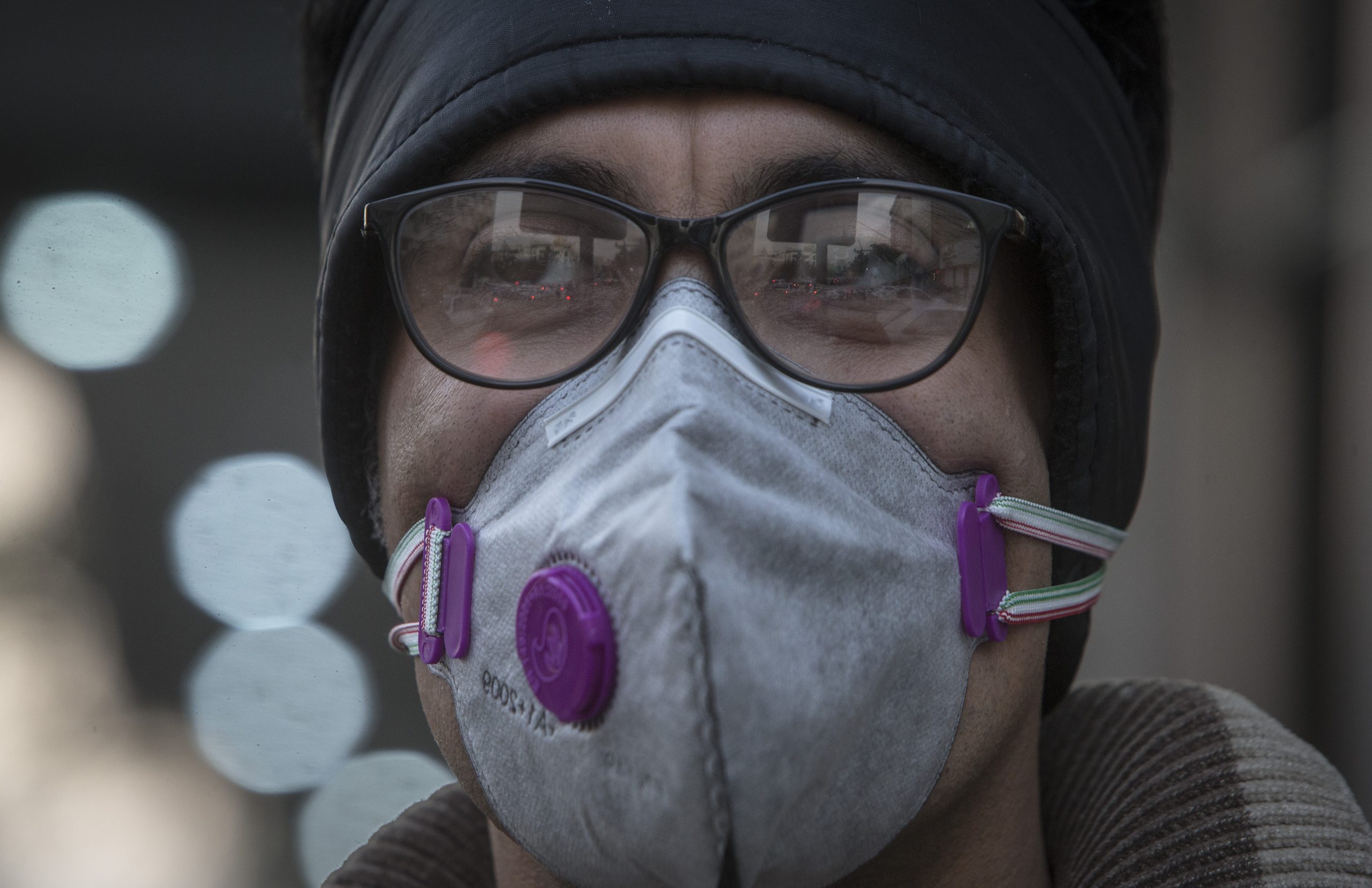

Researchers have found more evidence to suggest that long-term exposure to air pollution is a cause of premature death among older people.

The study, published in the journal ‘Sciences Advances’, provides the most comprehensive evidence till date of the causal link between long-term exposure to fine particulate (PM2.5) air pollution and premature death.

“Our new study included the largest-ever dataset of older Americans and used multiple analytical methods, including statistical methods, for causal inference,” said the study’s co-author Xiao Wu from the Harvard University in the US.

“The study shows that current US standards for PM2.5 concentrations are not protective enough and should be lowered to ensure that vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, are safe,” Wu added.

For the current study, researchers looked at 16 years’ worth of data from 68.5 million Medicare enrollees — 97 per cent of US citizens over the age of 65 — adjusting for factors such as body mass index, smoking, ethnicity, income and education.

They matched the participants’ zip codes with air pollution data gathered from locations across the US. In estimating daily levels of PM2.5 air pollution for each zip code, the researchers also took into account satellite data, land-use information, weather variables, and other factors.

They used two traditional statistical approaches as well as three state-of-the-art approaches aimed at teasing out cause and effect.

They used two traditional statistical approaches as well as three state-of-the-art approaches aimed at teasing out cause and effect.

The results were consistent across all five different types of analyses, offering what the authors called “the most robust and reproducible evidence to date” on the causal link between exposure to PM2.5 and mortality among Medicare enrollees — even at levels below the current US air quality standard of 12 Ig/m3 (12 micrograms per cubic metre) per year.

The authors found that an annual decrease of 10 Ig/m3 in PM2.5 pollution would lead to a 6 per cent-7 per cent decrease in mortality risk.

The authors included additional analyses focused on causation, which address the criticisms that traditional analytical methods are not sufficient to inform revisions of national air quality standards.

The new analyses enabled the researchers, in effect, to mimic a randomised study — considered the gold standard in assessing causality — thereby strengthening the finding of a link between air pollution and early death.